Disclosure: All opinions expressed in this article are my own, and represent no one but myself and not those of my current or any previous employers.

I’ve been meaning to write about this for a while now, and I never seem to get around to it, so here goes, finally.

More often than you’d think, I find myself in discussions around technology and architecture, and specifically (especially over the last decade), the topics of microservices and macroservices. When they do, I end up saying something like “well, even if you do all this stuff and that stuff and do it the right way, odds are it’ll get screwed up by not appreciating Conway’s Law.” And, understandably, the other people in the conversation nod and are just happy that I’ve (finally) shut up. Sometimes, someone will even ask me what I mean, or more realistically, consider asking and then stop themselves, happy that I’ve finally shut up.

This is Conway’s Law, by Melvin Conway:

| [O]rganizations which design systems (in the broad sense used here) are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations. |

Word, Melvin. Wait…is “word” still cool?

Microservices and Macroservices

I wrote another equally unreadable post somewhere else talking about Event Driven Architectures, and that conversation led to some definitions around the kissing architectural cousins, and because I’m lazy, I’ll just self-plagiarise.

|

In my experience, with microservices we risk creating services that are too fine-grained, leading to an explosion of services which are, in turn, hard to manage and maintain. This granularity can result in excessive communication overhead, as services need to frequently communicate over the network, and worse, it can also make the system as a whole harder to understand and debug. I also think, practically, that it leads to a need for more developers, especially if the company understands the impact of organisational structures on technology.

|

My preference is macroservices, or mini-monoliths, which provide a compelling solution to the challenges posed by overly fine-grained microservices by striking a balance between the monolithic and microservice architectures. By grouping related functionalities into larger services, macroservices reduce the proliferation of excessively small services, thereby mitigating the complexity and management challenges associated with handling numerous independent services. This approach lowers communication overhead, as there are fewer service-to-service interactions over the network, leading to improved performance and reduced latency. And, by consolidating related functionalities, macroservices simplify the system's architecture, making it easier to understand, debug, and maintain. |

|

In my experience, macroservices offer a more manageable and efficient architectural choice, providing the benefits of modularity and scalability without the extreme fragmentation and complexity that can accompany a microservices approach.

|

But I’m not sure that is enough, unfortunately (for the reader, that is), as I’ll ramble on about it a lot more, because it’s vital understanding for the rest of this nonsense. So, let’s establish the basics first.

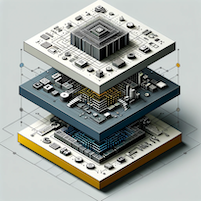

Microservices are a software architecture style in which complex applications are composed of small, independent processes communicating with each other using language-agnostic APIs and/or language-specific SDKs. These services are highly modular, each focusing on a single capability or function, and can be developed, deployed, and scaled independently. Furthermore, microservices can be used across applications.

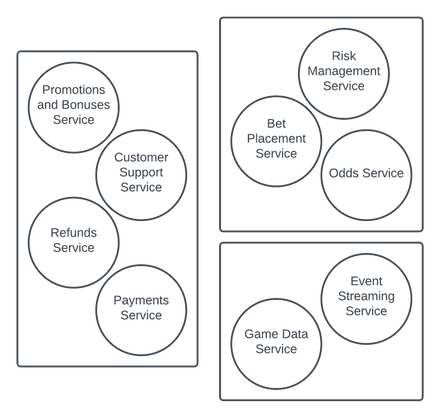

Because I would gamble on pretty much anything, let's use a sports book (in a casino, for instance) as an example. In a sports book, you might have a service responsible for calculating and updating the odds of various sports events based on a range of factors, including past outcomes, current bets placed, and real-time events. There are some key responsibilities of that service, including calculating initial odds based on various data and machine learning algorithms, updating those odds in real-time, reacting to the bets being made (balancing the book), adjusting odds for in-play betting, and so on.

That odds service will also have to interact with other services, such as the system that is providing it game-data to enable the real-time odds. That game-data service is responsible for live data capture of various sporting events, validating and processing that data, and serving it up to consumers, all while managing the elasticity and reliability of the service.

Still another service might do payments, perhaps another for refunds (for instances like a boxer is discovered throwing a fight, perhaps), and others for user accounts, bet placement, event-streaming, risk management, promotions and bonuses, customer support, etc. And by “etc.”, I mean that I probably haven’t named even half of them. The important point is that they each do one thing. That’s the micro part. They’re highly modular, because (e.g.) I might be able to use that payments service for other things at my fictitious casino, like online casino games (such as virtual slots), tournament entries for the Texas Hold ‘Em games I might run, retail purchases at my boutiques and restaurants, VIP services and subscriptions, a service for affiliate marketing programs, customer rewards, and tickets to Cirque du Soleil, and tickets to my elderly people mud wrestling events, which are more popular than they should be.

We can quickly imagine a whole bunch of different (again, single-purpose) microservices, and how they can create an insanely flexible, and massively robust system.

And therein lies part of the problem. In theory, this is an amazing architectural approach, and you can see why it’s so popular. Unfortunately, in practice, it often falls short, in my experience, and I’m going to talk about a couple reasons why.

Managing and coordinating multiple services, each with its own database, dependencies, and communication protocols, can introduce complexities in terms of deployment, monitoring, and debugging. There's also operational overhead, because with microservices, there is a need for additional infrastructure and tooling to manage service discovery, load balancing, and inter-service communication, which increases operational overhead and often requires specialised expertise. There are also challenges with testing and deployment, amongst other things. All of these things can be overcome. But it takes a lot to do so, and it’s often very expensive. And the vast majority don't overcome them, and the practitioners have battle wounds and the tech equivalent to PTSD.

Microservices are in some ways the architectural equivalent to XML. You get the concepts. It makes sense. For a while, it works. Then it’s a huge pain in the ass. And then it becomes an anchor. And then you’re suddenly as angry as Michael Bolton in Office Space.

But that isn’t why microservices fail. All of those things make stuff harder, but they don’t make it fail. I’ll get there, but first I want to contrast this to macroservices, which, admittedly, is nuanced and more than a bit fuzzy in terms of a well-defined concept. Thus, I’ll start with some analogies because those usually help (well, they help me, at least).

From an analogy perspective, let’s use LEGO. The individual block is the microservice. Yes, if all I have are little blocks you can make whatever you want, be it a car or a truck or a space machine, but honestly, the end product is usually better to buy a set and make that. The set is a macroservice. I have the VW Van in LEGO and it’s so cool.

I mean, sure, I could have just used the LEGO explanation to explain a lot of this from the start, and that would have saved reading an unnecessary 500+ words, but too bad. Now we’re in this thing together.

So a macroservice, then, if I’m continuing with the analogy route, is the LEGO box set, as opposed to the individual blocks. Or, it’s a fancy dinner, with each course being a microservice. Or, it’s the library, and each book is the microservice. I could continue, but if you don’t get the point yet, shame on both of us.

Like I said, it’s nuanced, so let’s talk about boundaries and how we determine them, since the boundaries seem to be the thing that differentiates microservices and macroservices (m*croservices, if you will), both in terms of where those boundaries exist as well as how we figure it out.

The best resource on Domain-Driven Design (DDD) that I have found is the amazing (and weirdly expensive) book: "Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software" by Eric Evans. The DDD approach is one of the best ways to determine where the bounds of your services should lie, and this is the bible on the subject. There is a lot of information packed into it, and I’m going to call out a small subset that I have found to be most important in practice, and the ones that lend themselves to my topic, beginning with bounded contexts.

Within DDD, defining clear boundaries around specific parts of the domain allows for focused development and minimal dependencies. In terms of microservices, each bounded context should have its own domain model and use a consistent language. When it comes to macroservices, I’ll loosen that latter requirement with a caveat, whereas in a microservice, I won’t. In a macroservice, or a mini-monolith, it’s not unreasonable to have “backend” code written in (e.g.) Python and frontend code written in (e.g.) Typescript, but that’s as far as I’d go (two) and only on macroservices where the domain is larger, and you can create distinctions within them. Those distinctions are usually around the superior tool for each job. In some cases, those macroservices may even have a mixture of architectural approaches, such as request/response on the frontend and more asynchronous processing occurring on the backend. Or, if, for instance, you had a number of microservices within that macroservice, then each microservice would have a ubiquitous language, and across the macroservices, there would be a maximum of two languages in total. But that’s just my own preference, and not some hard-and-fast rule. And it is mostly about maintenance.

If the m*croservice spectrum goes from an individual functionality on one end and “mini-monolith” on the other, I’m arguing for the “mini-monolith” side of it. Maybe with the sports book analogy I start to make decisions around combining certain microservices into macroservices, and I’m grouping by what development can happen with minimal dependencies and a shared domain model. Perhaps our earlier example might combine things to align to the groupings of what I’m showing here, and for full transparency, I debated whether refunds and payments belong with customer support and promotions. Still not sure I like it this way, but that’s the art of it (or so I tell myself).

One more thing: each of the microservices discussed earlier, and the macroservices I’m talking about now, are reusable across products that might need to leverage them. But what of those products themselves? How do they fit in?

For me, I have a hard line in the sand wherever business rules exist, and that, too, is a separate macroservice, together with the other similar things that aren’t reusable (use the same DDD domain model rule). If the functionality as a whole is reusable, then spin it off as a macroservice of its own, by recognising when that point to do so is: the first time it’s reused. I’ve been known to say “your code isn’t reusable until it’s the first time it’s reused”, which I don’t know is my own, or if I’ve subconsciously stolen it, or if it’s really all that interesting anyway. I hope it’s the first one, but I wouldn’t bet on it.

It’s okay for some macroservices to be reusable, and you’ve grouped like functionalities (which might otherwise be developed as microservices) together, and then you have this separate macroservice or macroservices where business rules and UIs are, and again, those are logically grouped, and they revolve around a single domain model. Obviously, that business rules macroservice lacks reusability, but reusability is not a requirement anyway.

Just to put a bow on this, business rules (in my definition) are specific to the functionality of a given product and are unlikely to be replicated across products. In my sports book analogy, I have a mobile app that is used to place bets, and that has business rules (things like cut off at the start of the match), but I also have an internal app that allows the internal bookies (who set the initial lines) to retrieve various bits of information to help them do that work. That application also has business rules, but they’re specific to the bookie offering, and the business rules for the latter differ from the aforementioned mobile app. They’d be two separate macroservices, each bounded by the business rules line and individual domain models in each.

Evans speaks to groupings in terms of “aggregates”, or clusters of domain objects that can be treated as a single unit. Domain objects here can be thought of as roughly individual microservices or functionalities. An aggregate has a root and a boundary, with the root being the only point of access from outside. The root becomes the equivalent to the queue, (AWS) S3 disk, (AWS) Eventbridge, Kafka, messaging hub, etc. Those are the points of access, and this is an important component of m*croservices.

And, it’s always worth noting when we get into this idea of points of access the famous (infamous?) Bezos email from 2002 (WTH…it has been twenty-two years ago already?!?!) that mandated how groups would thereafter interact, only via APIs (using the right definition, not the common mistake of “API” meaning “RESTful API”, which is just one type). I quote that email (emphasis mine):

1. All teams will henceforth expose their data and functionality through service interfaces.

2. Teams must communicate with each other through these interfaces.

3. There will be no other form of interprocess communication allowed: no direct linking, no direct reads of another team’s data store, no shared-memory model, no back-doors whatsoever. The only communication allowed is via service interface calls over the network.

4. It doesn’t matter what technology they use. HTTP, Corba, Pubsub, custom protocols — doesn’t matter.

5. All service interfaces, without exception, must be designed from the ground up to be externalizable. That is to say, the team must plan and design to be able to expose the interface to developers in the outside world. No exceptions.

6. Anyone who doesn’t do this will be fired.

Opinions may vary on the human being, but credit due: this was a pivotal e-mail, whose shockwaves have impacted how we interact with software today, and perfectly aligns with DDD and not only where the various m*croservices fit together, but vitally, how. It is not an exaggeration to say this email had a profound impact on my professional thinking, and I didn’t even work there!

To me, this is one of the great ways to think about how these things fit together, and key to that is this idea about point of access. It’s about the connection points, and standardising on those. Make that consistent (and use something like the patterns of Event Driven Architectures to connect them, for lots of reasons I cover elsewhere, and you have the foundation for a decoupled system that follows the right concepts, and one that can use the shared services without them being too fine grained as to become problematic from maintenance and extension perspectives. To that end, domain events are a means by way to trigger side effects across different parts of the system, further helping to decouple components and model real-world processes.

Finally, I want to call out, like Evans does, that of positioning things for “refactoring toward deeper insight”, which emphasises the importance of continuous refactoring to reflect a deeper understanding of the domain, which in turn improves the model's effectiveness and the software's alignment with business goals. These things need to be living and changing as we learn more, as other information is gathered, as systems change and technologies evolve, our systems should be flexible enough to do the same. If there would be one thing I’d say to someone who doesn’t get why technology is hard, it might be that the ground under tech has been moving and changing at a pace that no other industry can match in terms of speed plus longevity of constant change (or the angle of that exponential change). Make sure your systems are built with fundamental and simple concepts. That includes how we organise the teams to support them. More on this shortly.

Yikes. This paper isn’t even about microservices versus macroservices. Or Domain-Driven Design, or the patterns of evolution in technology. It’s about how Conway’s Law screws it all up. Or, more aptly, how many will because they don’t appreciate it enough.

So, I’ll leave section one (!) at this: macroservices are like mini-monoliths. They should still follow the spirit of a microservice by following the right DDD approach to determining their bounds, but the concept of a disciplined approach to determining those bounds is the same for both macroservices and microservices. And to be fair, there can be extenuating circumstances beyond DDD that might be a factor in determining bounds in your own bounded context, such as size/complexity, data ownership, and other things.

Getting to the actual subject of this (finally), is where we go from here, regardless of whether it’s microservices or macroservices, or some Frankenstein’s monster of both and ten other approaches…

Team Structures

For me personally, team structures are intentionally transient, with so many caveats coming. From a people management perspective, I’m like the baseball coach that plays with the lineup regularly, but always from an experimental standpoint using data. Not changing things for the sake of doing it. I don’t necessarily change the person who hits leadoff or the one that hits cleanup, if you will, but I will work with the lineup regularly to get it right, and then understanding that what works today might not have the same effectiveness in six months, I’ll change it again then. Side note: I live in New Zealand, and while few-to-none kiwis will likely see this, I should really explain that baseball analogy. I really should. Anyway...

The other benefit I personally find with making change the norm is that when team structures are forced to change (significant resignations, layoffs, funding issues, corporate restructures, etc.), the shock wave is lessened; explainable change is already the norm, and transparency is expected. I can’t stress how well this has worked for me from that standpoint. When I’ve worked in organisations that find significant change really hard, and then when something finally does happen, the entire place becomes a psst psst psst nightmare for a month and nothing gets done, except people chasing down incorrect assumptions, rumours, and gossip. And bullshit executive meetings where everyone is trying to read between the lines, some people know significantly more than others, and everyone else is confused. But at least everyone is super stressed, so everyone is on edge, too. Ugh.

Of course, some level of that is expected (and healthy). My point is that when chaos isn’t debilitating, it can lead to real focus, and preparing the teams offers many other upsides. We find those really good connections between folks, and their shared knowledge leads us to our collective adjacent possibles otherwise missed, which is where real innovation is born. And, we know who doesn’t work well together, and that’s pretty valuable, too.

Again, I’m not talking about changing teams week-to-week, or even project-to-project, because I think consistency is important, and because I lean towards “you built it, you maintain it” as the best way to make sure the code is easy to maintain (...well, I don’t want to wake up in the middle of the night when this things break…). What I am saying is that as an effective leader, you need to think of yourself as the coach of a team, and good teams realise everything changes, all the time. That’s a feature, not a bug. And as the coach, it’s your job to make sure that the lineup is the most effective one it can be. Sum of the parts and all that jazz.

But…the one rule I have when I play with team structures is to make sure that the team structures reflect the technical architecture. That’s actually the key here…that would be it. The rest of this is all me rambling on, as I have a bad habit of doing.

So the trick is to limit the people working on the macroservice to remain in that macroservice. They can shift (regularly, but not often) across those individual functionalities within the overall bounded context, and that helps for when (not if) staff changes. But, once someone shifts out of that bounded context, then they can’t support any of the functionality that resides within it. Hard stop. Because that’s where things break down.

Before the M*croservices

Critically important to understand here: most companies who have an idea and build a product build a monolith. I care about reusability, but if the product fails, nobody is reusing anything anyway, so…priorities. If that is your viewpoint: please, trust your instincts. Get to done. Get the product out there. Get it in front of customers. Almost every startup builds an idea and some ideas get funding or traction, and a small percentage of those ideas work. And when they start to, you start to realise that your code can probably only keep going like this for a while before we have to do some refactoring. We’re rebuilding functionalities that walk and talk like a duck but somehow don’t fly together. We seem to have multiple line items for the same types of services.

So when we start in the startup, everyone wears every hat. There aren’t quite enough hats to go around, or we don’t have the budget for more heads, or something like that. And we’re building stuff to fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. Everyone rightfully feels like they have the ability to move horizontally and vertically. I am not changing that. What I’m saying is that when you get to a certain size, your monolith startup shows needs/opportunities to reuse and consolidate. When that happens, you move those reusable pieces out, and a team begins to build out the connection points and the abstraction between the self-enclosed service and the outside world, if you will, and the rest of that monolith stays. A developer in that startup monolith still has the same upwards and horizontal set of career options, but they are within the realm of the bounded context. And, similarly, when individuals go to (or are hired to support) a new macroservice, that sets their new boundaries. Within that bounded context, there are various roles and jobs to be done, and movement within those can happen (e.g.) every six months, but it’s good to have consistency within that macroservice. Again, of course folks can leave a macroservice. If you’re reading like I’m putting your feet in concrete and saying “this is your permanent role and focus”, then I’m failing you, because that’s not my intent.

This feels like a good balance towards getting cross team support (multiple people within the team can support the front end and back end, if it’s a business rules bounded context, or across functionalities/services in a “reusable macroservice”), role movement and opportunity for the individuals, consistency within a macroservice, and the right levels of decoupling to make it all work.

Wasn’t This About Conway’s Law?

The problem really comes because organisations often create their structures out of business thinking. They put all the software developers together and call it “I.T.” (usually, this is because they were founded before 1989, and technology was only a means to an end) or “Engineering”, and in someone’s head, this made sense, because it works that way for Accounting, Finance, Human Resources, Marketing, etc.

And then within this high level technology group, teams got organised. Those team organisations often stemmed from project work. And a project isn’t just business rules; it’s also (at some stage in a company’s growth) doing work that can be reused. And eventually someone may have decided that they were going to put all the front end developers together, or all the Data folks together, or all the security folks together, or all the API and backend folks together, or all the database folks together…I could go on, but I trust that’s enough to prove the point. So now you have this Head of Engineering or CTO or whatever the highest level in your technology organisation is, and below them you have some shared resources who work in these generic “backend” or “data” horizontals, and within those, you also have managers and doers. And a doer might report to one manager but be seconded to a new project that the company deems important. And that is going to happen across various teams and across various horizontal job groupings and roles.

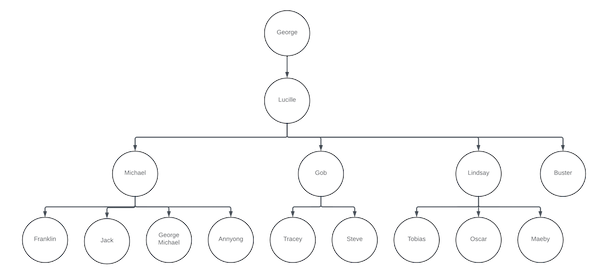

So what happens? Why is this bad? Well, because of Conway’s Law. It is not the fault of the people! It’s how humans are wired. Because the reporting structures reflect the way the business thinks, over time, the code will, too. And once that inevitability happens, your m*croservices will break down. Imagine this corporate structure for an IT department:

I’m not worrying about titles or roles here. I’m just illustrating to make a point.

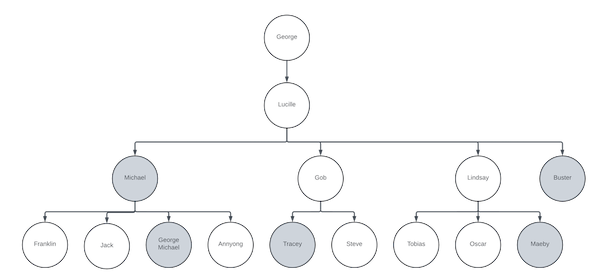

Now, let’s imagine that the following folks have all been assigned to work on some new and exciting project, called…The Banana Stand (obviously, if you recognise these names). Perhaps the following individuals have been chosen to line up the ones and the zeroes:

The Banana Stand is a mobile app, which offers exclusive deals, the ability to connect with other banana lovers, and a rewards program. Taking it a step further, let’s imagine that the team has identified a number of different microservices they want to build out to support the app, such as:

Banana Inventory Service: Manages the inventory of bananas, tracking the quantity, ripeness level, and expiration dates of bananas in stock.Banana Bucks Wallet Service: Handles transactions and balances for the digital currency used by customers to purchase bananas from the stand.

Banana Quality Assurance Service: Uses AI and computer vision to inspect each banana for optimal quality, ensuring only the finest bananas are sold to customers.

Banana Stand Reviews Service: Allows customers to leave reviews and ratings for their banana stand experience, including feedback on banana quality, and customer service.

Banana Stand Rewards Program Service: Manages a loyalty program for frequent banana stand customers, offering rewards such as free bananas, merchandise, or exclusive access to banana-themed events.

Banana Stand Merchandise Store Service: Offers a digital storefront for purchasing banana stand merchandise, including "There's Always Money in the Banana Stand" t-shirts, mugs, and novelty items.

Banana Stand Social Media Integration Service: Integrates with social media platforms to allow customers to share their banana stand experiences, photos, and banana-related puns with friends and followers.

The problem is that because (e.g.) George Michael worked on the Banana Bucks Wallet Service, and he also worked on the Banana Stand Social Media Integration Service, he’s going to eventually blur the lines between them, and they don’t follow the DDD guidelines, or share a domain model. Similarly, Maeby worked with Michael on the Banana Stand Merchandise Store Service, but because Michael is George Michael’s boss, those lines are going to blur, because they are going to eventually reflect the reporting lines.

They’re ultimately going to start to make design decisions that reflect the communication lines in the organisational hierarchy. Fer realzies.

In the end, you’re creating a monolith, despite all the best intentions. Or, a really jacked up set of microservices that don’t make sense and are hard to maintain, and even harder to extend.

And, that’s why I find doing microservices right so…damn…hard, and more importantly, so…damn…expensive. Because the way to make sure your designs are right and the right boundaries are respected is to assign developers to those services and keep them working within their bounded contexts. And, because you can never have a single person support a microservice (if she leaves or dies, you’re SOL), you need to have massive staff at scale. Let’s just say for the sake of conversation that each of the aforementioned services (of which I named seven) needs an average of three people. Now, this project needs twenty-one people just to support these services. And of course our fictitious company has more than just these services (after all, the Banana Stand isn’t the only revenue stream in the company), and with these twenty+ people focusing on those, we need more staff to build the mobile app, because that’s a macroservice in-and-of-itself.

And that, in a nutshell (banana peel? Wow…I definitely need sleep) is what the biggest problem with microservices is at scale: the number of people to support them. And if the solution to that is to not have folks dedicated to their bounded contexts, then you lose to Conway’s Law.

What is a Better Alternative?

Macroservices, for one. I’ve talked this to death, so I won’t waste too much more time on it, but if we instead create mini-monoliths of similar functionalities, we address the seven-services-to-twenty-one-people problem, so that’s a big step and a huge financial savings, but Conway still bites us in the ass. And the way to fix that is twofold: one, create your technology organisational structures to reflect your technology architecture. Cannot emphasise this enough. If you have macroservices, then you have to create organisational hierarchies that exactly reflect those macroservices. Hard stop. No other answer, and you can’t cheat on it, because humans are humans and humans are going to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures. So, if you want to make it work, flip it on its head and make your communication structures reflect your technical designs. And the second fix is to be willing to adjust your teams as your technologies evolve.

Remember this from about a trillion words ago:

These things need to be living and changing as we learn more, as other information is gathered, as systems change and technologies evolve, our systems should be flexible enough to do the same. Maybe it should be extended to say “our systems and our organisational structures should be flexible enough to do the same”.

Other Benefits

I’m sure there are more, but three obvious benefits that emerge when we align our organisational hierarchies around our services, and assure that our communication lines respect our bounded contexts: first, we end up with a flatter structure. It doesn’t forego the need for middle management, but it changes it. I tend to insist that management at that level (which is to say, direct managers of individual contributors) keep their hands on the keyboard. They might play a different role in terms of writing code, but they still do write code.

Secondly, in conjunction with a flatter structure, we push more of the decision making to the edges. Quick call out to the book Team of Teams, by General Stanley McChrystal, that focuses a great deal of time on this particular subject. This is actually a book I’ve gone so far as to buy for all the individuals in my teams who have people management responsibilities. Developing that trust is one thing, but the empowerment of it is even more powerful, because it creates the sense of ownership that matters most.

Finally, with the right bounded contexts, we create the right environment to lean into using the right technologies for each job. I can’t say enough how vital this is, and how it’s one of the ways that we really exploit the opportunities the cloud affords us. I talk about the olden days too much (get those kids off my lawn/turn down that poor excuse for music/in my day, we didn't need all these fancy gadgets and gizmos), but this one isn’t incorrectly pretending things used to be better (they weren’t - and if you think otherwise, read Factfulness. Actually, in any event, read it. You’ll feel better about the world). What I’m talking about is the olden days when we had a finite number of servers, and because of that, a finite number of software packages and approaches that we could apply to accomplishing the task at hand.

I’ll use databases as an example: we used to have to use relational databases, which are (still) ideal for data exploration and finding the signal in the noise, but comparatively horrible for individual access queries, where NoSQL shines. Or, we were stuck with relational databases for creating network graphs, where alternatives like graph databases shine. Or we were using ElasticSearch and Solr for search, whereas Lucene is a poor replacement for the semantic precision of a vector database. Or, we were using DBMS where what we really needed was inexpensive disk that still provided us accessibility, like S3. Worse, we couldn’t experiment to find out.

With m*croservices, we have the right boundaries to encourage using the exact right tools for the job. One service may benefit from a vector database, whereas another might find relational databases to be the perfect fit. Each service has to retain their own data stores, because Bezos said “no back-doors whatsoever” (in my humble opinion, the most important words in his email), but that becomes another feature of it. It empowers us to select the right tools for the job, and the cloud makes it trivial to stand up those tools (and equally, to destroy them if we want to try something else). Use this superpower.

That’s it. I’m glad I finally wrote this. And that makes one of us. Thanks for reading.

Joel Lieser

Joel Lieser