Disclosure: All opinions expressed in this article are my own, and represent no one but myself and not those of my current or any previous employers.

I am forever thankful for having had the opportunity to work with, and learn from many of my former colleagues at Netflix, and it’s impossible for me to pick what was piece of advice had the biggest impact, but I’m very sure that this nugget is in the the team picture:

| Now that you’re a manager, your first priority is talent acquisition. Your second priority is talent acquisition. Your third priority is talent acquisition. After that, it’s the rest of your job. |

Could. Not. Agree. More.

And I do my best to live it. I pride myself that my superpower is the ability to create high performing teams. Actually, that’s bullshit. That’s not a superpower; it’s just being really disciplined to never shift from setting a high bar and doing everything I can to assure every hire exceeds it, and an ongoing focus on continuing to raise that bar. It’s about creating the time to network and to interview, to send emails and follow up emails. It’s about never compromising, no matter how long it takes. And I am incredibly proud of the level of talent that I’ve been lucky enough to be able to attract and retain across a number of organisations in my career.

With that context, you can imagine how devastated I was when I recently spoke with a person from a previous career stop that said to me (paraphrasing): you did a great job building a high-performing team, but you didn’t do a good job promoting folks to replace you. It turns out that a couple of folks that I identified as people to handle a number of tasks I had been performing before I departed were struggling to find early success, which this person clearly blamed me for! Now, it is worth mentioning some things: (1) I felt like I could point to a number of really successful people that I was lucky enough to watch move up the corporate ladder who had tons of success, so my immediate feeling was to hit back with counter data points (I didn’t). (2) They might be right. Maybe this is a weakness of mine, and it’s absolutely, positively feedback that I have taken on board. Also, (3) it is worth stating unequivocally that at least one of these folks who were struggling have since found their footing, as I understand it. But I’ve reflected a lot on this feedback, and have come up with some hypotheses as to other factors that might be at play when folks fail in new roles (in addition to how I can personally improve at both promoting and supporting them), and I want to talk a bit about some of that here.

The Peter Principle

Okay, so everyone knows this one, but I’ll call out the Wikipedia version here, so we’ve got a shared baseline to start from:

| The Peter principle is a concept in management developed by Laurence J. Peter which observes that people in a hierarchy tend to rise to "a level of respective incompetence": employees are promoted based on their success in previous jobs until they reach a level at which they are no longer competent, as skills in one job do not necessarily translate to another. |

Oof. Worse: it’s hard to argue the accuracy of it.

I’m going to contend here why this is so much more pronounced in technology, and what we can do to battle it. This is certainly a departure from my normal technology rants, but as a people manager, it’s an important discussion to have, even if it’s one sided (keyboard warrior).

But I am going to stick to my lane in terms of this discussion by focusing only on roles within technology, since it’s just about the only thing that I’ve accumulated enough career capital in to consider myself anything close to an expert in.

Technology Career Paths

We have to start by talking about the major deficiency in technology career paths, which is that in almost every organisation, there is sadly but one path after a certain point, which is such a dramatic departure from the different roles that might get you there.

As a technologist, I think it’s important to take a second to appreciate our parents; most of which are incredibly confused about what we do. I mean, I’ve been in technology since the mid-1990s (I specify the century because I look old enough that it could be the 1800s), and my folks still somehow think I know a lot more about printers than I do, or their modem, and somehow, they think I have the phone number to Google, for when they don’t get the right search results back and “just want to talk to someone there.” Who am I kidding? It’s probably Internet Explorer.

Top of mind, I can come up with all sorts of roles (specialities) in technology, including but not limited to: Solutions Architect, Web Developer, Software Engineer, Data Scientist, Cybersecurity Analyst, Network Engineer, Cloud Engineer, Database Administrator (DBA), DevOps Engineer, Systems Administrator, Mobile App Developer, UI/UX Designer, Machine Learning Engineer, Quality Assurance Engineer, Business Intelligence Analyst, IT Support Specialist, Blockchain Developer, Frontend Developer, Backend Developer, Full-Stack Developer, Automation Engineer, API Developer, and Data Engineer. Collectively, I’m just going to use the term “Developer” because it’s easiest, and when I do, I mean one of these (or one that isn’t listed).

And what is the path for each of them? Well, in 99% of companies, they spend a few years, then become a “Lead”, and then become a Staff Manager. I don’t necessarily care about the actual titles, but those are the roles. So, let’s delve a bit deeper into the skill sets of these folks, and what they’re expected to do.

Developer

As a Developer, individuals are expected to possess strong coding skills and expertise in various programming languages, frameworks, and technologies relevant to their specific role, whether it be frontend development, data engineering, or blockchain (etc.). They are responsible for designing, implementing, and maintaining software solutions, applications, or systems according to project requirements and specifications. Developers collaborate closely with other team members, such as UI/UX designers, data scientists, and quality assurance engineers, to ensure the successful delivery of projects. Additionally, developers must demonstrate problem-solving abilities, attention to detail, and a commitment to continuous learning and improvement to stay updated with emerging technologies and best practices in software development.

Lead

A Lead Developer assumes additional responsibilities beyond coding and technical implementation, taking on a leadership role within the development team. In addition to possessing advanced technical skills and expertise, Lead Developers are expected to provide guidance, mentorship, and technical direction to junior developers and team members. They play a crucial role in project planning, architecture design, and code reviews, ensuring that development efforts align with business goals, industry standards, and best practices. Lead Developers also collaborate closely with stakeholders, project managers, and other departments to communicate project progress, address technical challenges, and make informed decisions that drive project success.

Staff Manager

As a Staff Manager overseeing developer and lead roles (meaning: individual contributors), individuals are responsible for managing and leading a team of Developers and Lead Developers to deliver high-quality software solutions on time and within budget. This role requires strong managerial skills, including the ability to motivate and inspire team members, foster a collaborative and inclusive work environment, and provide constructive feedback and performance evaluations. Staff Managers also play a larger role in talent acquisition, resource allocation, and capacity planning, ensuring that the team has the necessary skills and resources to meet project requirements and organisational objectives. Additionally, they are responsible for setting and communicating team goals, defining project priorities, and facilitating communication and collaboration across different teams and departments to drive alignment and synergy within the organisation.

Succinctly, success is judged by:

Worth noting, I’ve always been transparent with folks around that Staff Management role. It’s not a strategic position. It’s an administrative one. Of course, this doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t be thinking strategically, offering opinions and ideas, etc. Rather, it simply means they’re not being judged on that. Yes, startups rules differ (they always do) because (usually) budgets are tight, staff sizes are small, and a more strategic position (such as the CTO) is probably also managing individual contributors. But this particular post isn’t about startups, per se (though this post is still equally applicable) so don’t call me out on technicalities. We’re talking about my hypothesis here, so please try and think about it objectively and in a slightly more abstracted manner. And be nice.

Okay, so with that established, it’s important to recognise that this middle management role (“Staff Manager”) is, in my opinion, harder for technology individual contributors to transition into than it is in other departments, for a simple reason: technology folks, by and large, are more introverted and individual. I mean…I suspect there aren’t that many super extroverted accountants, either, but see earlier request to be nice.

Anywho…development is an individual activity (please do not throw “pair programming” at me. Pair programming requires two developers to work closely together, which leads to reduced individual productivity and autonomy. It doesn't suit every developer's working style or preferences. Some developers may thrive in a more independent environment where they can focus solely on coding tasks without the need for constant communication or consensus-building. Moreover, pair programming is unnecessarily resource-intensive, requiring double the humanpower for every task.

If you need your hand held to do a one-person job, you should find a different line of work. Yeah, that's harsh, and yes, I understand that it's Junior Developers that significantly benefit from this approach, but I also don't hire Juniors anymore because they don't move the needle. Another post for another day, and while my opinions might piss you off, hopefully you can at least appreciate that I'm willing to share them. And I'm right, so I have that going for me).

Development, by its nature, is a predominantly individual activity that often attracts individuals with introverted tendencies and similar qualities. The process of writing code requires deep concentration, problem-solving skills, and a high level of attention to detail, qualities that are commonly associated with introverted personalities. Introverts tend to thrive in environments where they can work independently, focus deeply on their tasks, and engage in introspective thinking, all of which are essential aspects of software development. Furthermore, the prevalence of remote work and flexible scheduling in the tech industry allows developers to create optimal working conditions that cater to their introverted tendencies, fostering a productive and conducive environment for deep work and creativity. As a result, introversion can be seen as an asset rather than a limitation in the field of software development, enabling individuals to excel in their roles and contribute meaningfully to the success of projects.

The transition to Development Lead is a pretty easy one to understand: it happens because the Developer showed strong aptitude and a willingness to share their strengths with others who need it. Easy peasy, so long as they aren’t pricks about it.

But that transition to Manager is harder for all the same reasons. While individuals can (and should!) have empathy, it becomes a whole different world at the Manager level, for all sorts of reasons. To be fair and transparent, I also insist that my Staff Managers keep their hands on the keyboard. Part of the reason for this is that (as already stated) this is not a strategic position, per se. And the reason they are taking this opportunity is because they’ve shown aptitude in development, and expressed a desire to move into a people management role. And vitally, I do not want to remove the skills that got them here. Instead, I’m saying that their first responsibility is now talent acquisition. Their second responsibility is talent acquisition. Their third responsibility is talent acquisition. After that, it’s the rest of their job. And that includes the administrative side of it. And if you think I’m asking an awful lot of this person moving into their Staff Manager role, I’m nodding. It is. And it’s a big reason why I never want a Staff Manager to have more than a handful of direct reports. Ever. They won’t be as effective, hard stop.

It’s another blog post (one I’ve actually written, and I don’t fault you for not having read it) about how I assure that team sizes remain that small, and it’s about respecting Conways Law and flipping the problem on its head, and designing your organisational structures to reflect your technology designs. I’d say it’s worth checking out, but I’d be full of shit. Another sigh.

That desire to ensure they continue to perform some set of duties that they excel at, which is to say the software development side of things, is one of the reasons that the Peter Principle doesn’t affect developers at this level as much as it will later on, so I think that is something that is key. Now, my reader (singular) might have a retort like “maybe the person isn’t great at software development, but they are great at people management”, which I completely hear you on! And I support those people becoming managers! I just don’t want them to become Staff Managers in my software organisation, because (by my earlier definition), they can’t do a significant part of the job, so they are already failing my expectations. Again, you might not agree with my opinions, but nobody is forcing you to read this. And, I’m right.

So, in my (very non-academic) research, and leaning on my own personal data points, I’ve seen plenty of Staff Managers fail. But it’s almost always the result of one of two factors:

1. It is more administrative than strategic, and the administration sucks. Managing holiday time and giving constant feedback isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. A lot of folks would rather be in control of their own destinies, and that means being an individual contributor, where you’re judged on your ability to deliver on your tasks and commitments, not on the successes or failures of others, or they don’t want to spend 10-20 hours a week (yep!) networking and interviewing and interview prepping, and so on

-or-

2. They aren’t good at it. See earlier discussion about introverts and general characteristics of developers. Side note: often times, this manifests itself in an inability to give difficult feedback, which is a skill in and of itself

But this isn’t even the point of this post, since these aren’t failures attributed to the Peter Principle, in my opinion, though the savvy reader will point out that #2 above is pretty much saying that the person has reached ”a level of respective incompetence.” However, I disagree, because I think if the person isn’t good at it because they aren’t actually good at software development (even at an individual contributor level) then the mistake was in the promotion, not the individual who was promoted, and if the reason for failure is that they can’t do things like give difficult feedback, that isn’t so much a skill as an individual decision. Yes, they might need support to learn how to do it, but everyone has the internal capacity to be honest. I argue that at this level and beyond, it’s more than a capacity to do so, it’s a requirement. But I also see a failure of doing so as a choice, not incompetence.

First, the Easily Fixable Problem

Before moving on to the Peter Principle within technology (holy shit…we’re not even there yet?!?!), let’s talk about how to solve this particular problem, which isn’t hard to do! The solution is to create other career paths for individual contributors who want to remain in technology, but may no longer want to line up the ones and zeroes.

Create a career ladder for technology roles that mirror the levels of people management, and then (vitally) acknowledge and respect those levels.

I’m going to spend a second to call out what this is absolutely, positively not. This is not some bullshit matrix that includes things like Developer I, II, III, IV and V. My blood pressure rises at how stupid those things are to me. They’re completely worthless, beyond that when your developers leave your organisation they can claim “I was a Developer IV” to their new employer. That new employer should respond with “what the f**k does that mean?”, to which the developer, if they’re being honest, should shrug and say that it means they checked some arbitrary boxes on a stupid spreadsheet and that it actually means nothing. Especially since the stupid checkboxes on the new company’s stupid spreadsheet almost surely don’t match the stupid checkboxes on the old company’s stupid spreadsheet. It’s title inflation. That’s all it is. Stop being part of the problem. You aren’t helping anyone, and you’re going to hurt your arm trying to pat yourself on the back.

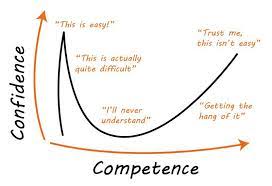

The other mistake is “Junior/Intermediate/Lead/Senior/Blah blah blah” or similar. Sure, the developer who just graduated from university initially is okay being called a “Junior” (with zero applicable skills, by the way. And that isn’t the developer’s fault: our universities need to do better by these kids. Here’s a starting point: at least teach Github…but I digress), but after that they aren’t. By then, they’re very confidently along the Dunning Kruger path (credit):

And they’re arguing that they need to better understand what it takes to get to the next level, and they don’t accept the honest response: time. Side note, if you have this situation and the individual is receptive to honesty and is a reader, I highly recommend So Good They Can't Ignore You. I think Newport gets more credit for Deep Work, but I have always appreciated the former to the latter. Let’s get back on task here, people!

What’s the right solution? It’s to put the time in, and make no mistake: it’s a lot of time. Create the paths, but don’t make them bullshit titles. Align them next to people management roles. When I worked at Nike, I had a Director level role, but Directors had people management responsibilities which I did not (at least initially). My title was super lame (Expert Engineer), but at least they had created a number of paths and roles for individual contributors to follow that equated to “not writing code any longer, but still doing technology stuff, and not managing humans.” For full transparency/completeness, Nike also didn’t require their technology managers to have shown any semblance of skills in technology, and too many of them that I encountered seemed to convey that ignorance and incompetence in technology was some sort of prerequisite to managing software developers, which had the effect you would expect. Hopefully they’ve fixed that now (I am a stockholder and huge fan of the company), but it was a cultural challenge when I was there, and so I doubt it. And before anyone gets upset, I’m not saying all the Software Engineering Managers were incompetent. It’s an attractive place to work. I just think when they got it right, it was too often by accident, or incorrectly tied to tenure, that’s all.

So, how do we avoid title inflation but accomplish creating paths for our tech folks? I think it’s about striving to flatten the organisation as much as possible (how flat completely depends on your organisation), then creating levels that match that degree of flatness, and then creating roles within those levels that have different expectations. And those expectations cannot be boxes to be checked. They have to be more aligned to both outcomes and how we get there. And how fast we get there. And how often it happens. Let’s use an example and see if it clarifies. Don’t get your hopes up.

I think Solution Architecture is one of those roles. It’s absolutely one of the most important roles in all of technology. It requires a depth of understanding that is achieved both through years and years of practical experience and an ongoing investment in emerging trends and technologies. It absofuckinglutely is not akin to getting a stupid certification, which does little more than prove you read a book about the different services that your cloud provider of choice put out. If you think that this is a sore spot for me, trust your instinct. Nothing drives me more crazy when I see candidates that think memorising some facts from a book as the equivalent to knowledge gained through years of dedicated practical experience as being the same thing, except, of course, the companies that fall for it. Or solution architecture committees. Hint: if your company has a solution architecture committee, your company doesn’t do technology very well, because those committees (in my experience at multiple stops in multiple US states and multiple countries across multiple industries) are filled with pricks who only ever bring two things to the table in spades: slowness and arrogance. But they read a lot of McKenzie blogs [just imagine a really big eye roll emoji here!].

Anywhoooooo, we can create a set of expectations for a Solutions Architect, and we can measure how effective the individual is in that role. It might not be the most quantitative analysis, but hey, most of this stuff isn’t actually all that quantitative, and that’s okay. We’re talking about judging the effectiveness of other humans here, and that is going to be inherently subjective.

I’m going to move on, because I eventually have to finish this. Weirdly, I expected this one to be less wordy. What a stupid I am (shout out to Roberto De Vicenzo)!

Huh. I wonder if I’d been able to tell him before his death in 2017 that he’d be referenced in a technology blog about the Peter Principle, he’d have said “eres un idiota”, and he’d be right.

Moving on.

It’s really about the next step beyond Staff Manager that I find problematic as it pertains to the Peter Principle. It’s that step where we ask technology professionals to fully take their hands off the keyboard. I think it’s less problematic in my Solutions Architect example, since success in that role requires ongoing investment and effort in technology, and specifically, in technology that the individual may not have hands-on-keyboard experience doing.

But what about as an individual moves into, say, a Head of role, or a CTO role. And again, not so much in a six person startup, because the CTO there is still a Staff Manager over the developers. But as the teams grow and we start to split out reusability across services, which in turn dictate our team sizes, we will inevitably eventually have a need for folks in other roles that don’t include checking code into repositories.

If we thought the transition to Staff Manager showed cracks in the foundation, yikes. This one is a full-on sinkhole. Gulp!

Creating the Lists

This is really what the focus of this long post is about. We’ve taken people who generally were successful in their careers because the following were ALL true:

(1) They were good Developers, by our earlier definition. They were judged on their ability to be successful performing the tasks given to them

(2) They moved into a Lead role and they helped other individual contributors be successful, by enabling said individual contributors to be successful in performing the tasks given to them. Their success was judged a combination of completing the task list given to them and helping others complete the lists of tasks given to them

(3) They moved into a Staff Manager role, which involved taking a superset of lists given to them and organising into smaller lists of tasks, which they in turn handed out to Developers. They’re judged by their ability to do talent acquisition, do administrative duties, and by them completing their task lists and by their developers completing their task lists. And for me, they still write (some) code, so they’re also subject to (1) and (2)

Now comes the hard part: the next step isn’t being given a list. They have to create the list.

While individuals may excel at completing tasks within their area of expertise, transitioning to a role where they must define objectives, set priorities, and establish strategic direction can be challenging. This requires a different skill set altogether, one that encompasses strategic thinking, decision-making, and leadership abilities. Unfortunately, the criteria for success in previous roles, focused primarily on task completion and individual contributions, may not adequately prepare individuals for the complexities of leadership and strategic planning. As a result, they may struggle to effectively define and prioritise objectives, leading to inefficiencies, misalignment, and ultimately, failure to deliver desired outcomes.

The ambiguity is at the heart of it. It’s so different from being given a set of instructions and then being judged on your ability to complete them. Equally, though (I’d argue moreso) is that you’re now being judged on your opinions, and opinions are often wrong. Especially mine.

I’m all about experimentation, and as my staffs (past and present) will undoubtedly contend that I never get upset or frustrated at “good failure” (I will however, give feedback when failure results from a lack of planning, a lack of effort, or other avoidable reasons), but as someone who is driving the task lists of whole teams (which is to say, driving strategy) and those opinions in turn have huge costs, both in monetary terms and in time, to say nothing of missed opportunities that fall by the wayside because our focus was on other things. So, on some level, you are very much going to be judged on your ability to be right in the face of ambiguity and in the faces of ambivalence and indeterminacy. How often you’re right, and which ones you get right and get wrong all come into it, too.

And that, my dear reader (still, singular :/ ) is why The Peter Principle hits technology folks differently. Not because others moving up the corporate ladder aren’t being faced with this same level of ambiguity; far from it. That part is consistent for everyone. Rather, it’s because of the combination of that plus where our dear software engineers came from: a world in which they’re performing (or supporting and overseeing) sets of tasks that are inherently deterministic.

Unlike many other industries where roles may involve more abstract or qualitative decision-making processes, technology roles often revolve around executing tasks with clear inputs, processes, and outputs. Software engineers are accustomed to working in environments where problems are approached methodically, solutions are based on logical reasoning, and outcomes are predictable. Thus, when faced with the ambiguity of defining objectives and setting priorities in leadership roles, technology professionals may find themselves grappling with a significant departure from their accustomed deterministic mindset. This shift can be disorienting and challenging, as it requires embracing uncertainty and ambiguity in a way that may feel foreign and uncomfortable.

And then they struggle. All that is pretty natural, and I’ve not said anything profound or groundbreaking here. But it’s important to define the problem, and more importantly, to talk about the solution, so I’ll do that next.

The Solution

This part is easy to define, but harder to do. Foremost, acknowledge it and communicate about it regularly (easy peasy). Talk about it. Discuss those challenges. Discuss the options, and the reasoning for the decisions. Show some vulnerability. Be honest about the challenges you’re facing or that you notice the other individual is facing.

And then, vitally, set about rectifying it. This part is going to be more nebulous, of course, because how we bridge knowledge gaps is a very individual thing. For me personally, it starts with the written word. I prefer to build a foundation of understanding either through reading, or through hands-on trial and error. Unfortunately, while the latter works fantastically for Developers, the uncertainty and indeterminate nature of this situation prevents that from being a practical path. But there are plenty of different books on the subject, and those are (again, for me, personally) the right starting point.

The other thing that helps me is mentorship. Having someone who has been there, or who specialises in these sorts of things can be indispensable. Much like a therapist, if nothing else, they get you talking about the stuff that is often hard to talk about, and oftentimes, that’s enough to help you make sense of things that were otherwise all jumbled around in your head.

So, if you’re facing the Peter Principle, unfortunately I can’t provide a prescription to avoid it. It’s too personal a solution for a common problem. But if you are the company, then you have a very real responsibility to support your staff members.

That support can come in many forms. One of those forms should absolutely be this: provide them a path back. Please. Remove any stigma about “demotion”, because this ain’t that. This should be viewed more like “we’re going to see how you like this role and how effective you are at it”, and give folks their dignity: always let them be seen as the decision maker if it isn’t working. Even when it’s not. Do not forget that they were incredibly valuable individual contributors and/or they were incredibly valuable managers of individual contributors. Let them go back to that and be successful again. Again, give them their dignity and let them be professionally fulfilled.

Remove the belief that a Manager label (at any level) is in any way “better” than a different role in the organisation (it isn’t). Yes, some roles get paid more than others, but that’s because there should be an understanding that the role has an outsized impact on revenue (or similar), not because the alternative isn’t valuable/required/necessary. Make that your culture: a culture of respect. At a minimum, that will make movement in any direction across your organisation safe. If we had a fantastic Developer who wanted to make a horizontal transition into a position in, say, Marketing, and they hated it, we’d of course welcome them back to their technology role, and most folks would shrug it off as “good on you for finding out.” There really needn’t be any reason that the same mentality can’t exist when it comes to vertical organisational movement, both directions. And it reinforces that culture of experimentation, which is really, really, really important.

And the other thing is to recognise and appreciate the Peter Principle. Understand that it is real, and support your people. This is new to them, and we want them to be successful. The bottom line is that when they fail, you’ve failed them, and you’ve not lived up to your end of the bargain.

If you’re the person in a new list creator role and you’re aware of the risk that you’ve been promoted to a position where you’re no longer going to be competent, remember this: it is your responsibility, and solely your responsibility, to avoid it. Yes, both things can be true. It can be on the organisation to support you and it can be on you to walk through the door. Your employer can’t determine if you prefer books or videos or classes or support groups or mentors or anything else (or any combination). And it’s not on them to (e.g.) buy or read you books. You chose to take this role on. Now choose to be good at it, and that means doing whatever it takes to gain competence. Make the same type of commitment you had to make to be too good to be ignored as an individual contributor. It’s on you.

So, when I was told that I don’t hire well, and then gave it some thought (based on the length of this post, a lot of thought!), I got over my initial defensive thoughts, and I now accept my own shortcomings, and I’ve vowed not to let it happen again. I’m going to be more deliberate in my choices, and I’m going to communicate better (and more). And I’m going to support those people in any and every way I can, including some honest feedback, both around where I see their struggles, and that it’s ultimately on them to fix it, but that I’m going to be there to help.

Thank you for your time in reading this. Together, we can create better work environments.

Me

Me